There are 333 members of the Baseball Hall of Fame. That includes players, executives, pioneers, managers, and umpires. Joe Morgan, one of those 333, wrote a letter to Hall of Fame voters in 2017 in which he states that he speaks on behalf of “many Hall of Fame members” when he says “Steroid users don’t belong here.” He says, “We hope the day never comes when known steroid users are voted into the Hall of Fame. They cheated.”

Joe Posnanski often writes that the argument over who to induct comes down to how you view the Hall of Fame. Do you view the Hall as a reward, a place to honor the greats? Or do you view the Hall as a museum, a place of historical record? But, I think there’s one more question that gets left out: Who is Cooperstown for? Is it for the 333 members of the hall? The 73 living members? Joe Morgan? Or is it for the tens of thousands of annual visitors? Is it for the hundreds of thousands who like to debate the Hall of Fame? It seems like a bad business model to base your voting and decisions on the desires of the 73 living members over the larger group of annual visitors.

I’m pretty sure the members of the Hall of Fame don’t even have to pay for admission.

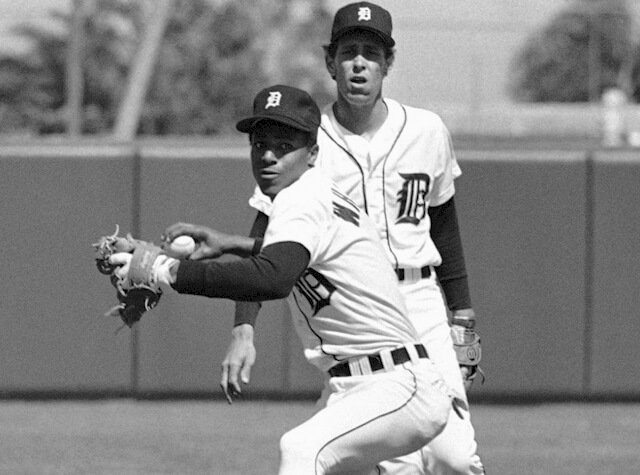

This is all to say that if the Hall of Fame is for the enjoyment of the fans, then the focus should be on the enjoyment of the fans. It opens up the possibilities in ways the sometimes stuffy Hall of Fame has overlooked. All of which brings me to Lou Whitaker. Sweet Lou has a very strong Hall of Fame case. He was a rookie of the year, a five time all star, four time silver slugger, fourth in Tigers history in WAR (the reason he was my choice for the bookmark having the highest career WAR of any Tiger for whom I had a card), and three time gold glove winner. In fact, the only reason he didn’t win more gold gloves is he played at the same time as Frank White and Harold Reynolds. From 1978, Whitaker’s rookie year, to 1990, the three slick fielders won every American League gold glove for second base.

Lou Whitaker and Alan Trammell both made their major league debut in 1977 and became every day players in 1978. And for the next 18 seasons they would be the starting middle infield for the Tigers, combining for 11 all star appearances, seven silver slugger awards, one World Series victory, and seven gold gloves. In 1983 and 1984 they both won the gold glove. They hold the American League record for games played together by teammates and the Major League record for double plays turned by a shortstop-second base combo. Both players have a case for the Hall of Fame as individual players. But it seems like the Hall of Fame has missed an opportunity to induct them together as a double play combo. They could share a plaque where they are turning a double play. I’d bet that plaque would be photographed as much as any other.

Here’s a little game Joe Posnanski likes to play. One of these two players is in the Hall of Fame.

Player A: 2,293 games played, 1,231 runs, 1,003 RBI, 412 doubles, 55 triples, 185 home runs, 3,442 total bases, .285 AVG/.352 OBP/.415 SLG/.767 OPS

Player B: 2,390 games played, 1,386 runs, 1,084 RBI, 420 doubles, 65 triples, 244 home runs, 3,651 total bases, .276/.363/.426/.789

You’ve probably guessed that player A is Hall of Famer Alan Trammell, and player B is Sweet Lou Whitaker. I left out the numbers that would’ve given it away. Alan Trammell’s career WAR is 70.7 to Whitaker’s 75.1. There’s a very real possibility that Lou Whitaker will one day be elected to the Hall of Fame, but I think the Hall is lessened by the two players not being enshrined together as the greatest enduring double play combo in baseball history. And I believe thinking like that would enliven the Hall of Fame allowing for other unique and enjoyable tributes to the game.

There’s also this: according to his 1988 Score card that I used as a bookmark, Sweet Lou played an astounding 252 games in 1985. You would think he would’ve set career highs in a few statistical categories with that many games played.

Lou Whitaker’s career WAR is twenty points higher than Hank Greenberg’s, but much of that comes down to the nearly four full years and another half season Greenberg missed when he was serving during World War II. In fact, despite his missed time, he was fifth on the all time home run list when he retired with 331 home runs, and doesn’t that number seem awfully cute today. He is still sixth for career slugging percentage. And he did it all not only as the first major Jewish star in baseball, but in a town and an era rife with anti-Semitism. His prime years coincided with Hitler’s rise to power, and he played in the town of Henry Ford and Charles Coughlin. After Kristallnacht, Coughlin led a march through Detroit where participants shouted, “send Jews back where they came from in leaky boats.” Greenberg received treatment at Henry Ford Hospital, a place named after a man who said, “If fans wish to know the trouble with American baseball they have it in three words – too much Jew.”

It is likely this discrimination and prejudice that helped Greenberg be on the right side of integration, both as a player when he shared the field with Jackie Robinson in 1947, and as a general manager with Cleveland after his retirement from playing. During his first year as GM he discovered his Black players were staying at separate hotels from the White players in several towns, so he insisted his traveling secretary find hotels that would accommodate the entire team the following year, no exceptions. When Hank was criticized for having five Black players on the roster at one time, he shot back, “the only time the fans complain is when the Negroes aren’t delivering.” The Black newspaper Cleveland Call & Post declared Hank was “a friend to the race.”

Greenberg was also on the progressive side of matters when it came to innovation in the game. He was an early proponent of interleague play and was one of only four people to testify on behalf of Curt Flood against the reserve clause. Ultimately, though, his time as a general manager with Cleveland was seen as a failure, and Hank harbored ill will towards the club and the city after being removed against his wishes. He said, “The only way I’d come back to Cleveland is if the plane goes down while I’m passing over the city on my way to New York.”

Which, of course, reminds me of future Hall of Famer Ichiro Suzuki who most certainly would sympathize. Ichiro once said, “If I ever saw myself saying I’m excited going to Cleveland, I’d punch myself in the face, because I’m lying”

Trammell probably got into the Hall more easily due to the “received wisdom” that Shortstop is a more difficult position, and therefore the second baseman’s gold gloves do not count for as much. As a former shortstop, what do you think?

LikeLike

I think Trammell definitely benefited from the extra attention and importance placed on the shortstop position, both in his eventual HOF induction and the recognition he achieved at the time. Much of what Lou Whitaker did made him just as valuable but was not as appreciated or even as quantifiable at the time. But do I think shortstop is a more difficult position and the gold glove means a little more? Yes, I think so. I think to play the position well requires a little more range, a stronger arm, less room for error than playing on the other side of the bag.

LikeLike